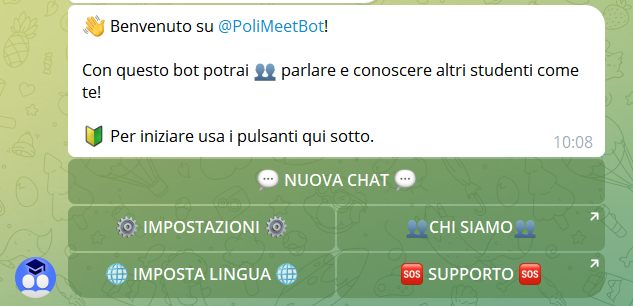

How we accidentally made a dating app for our University Campus.

We didn't expect this social experiment to go this far.

Two years ago, a couple of friends and I from university decided to start PoliMeet. What began as a small side project evolved into something much bigger — a sort of anonymous dating app for our university campus. This is the story of how that happened.

The logo we used for the bot.

Inspiration: The Chat Incognito Bot

The initial idea for PoliMeet came from a bot already existing on Telegram called Chat Incognito Bot. This bot is essentially a text-based version of Omegle, though it's notorious for being overrun with spam. The concept is simple: launch the bot, click a button, and get matched anonymously with another user. You chat, meet someone new, and then move on to the next conversation.

I thought, "Why not take this idea and adapt it specifically for our university campus?" The goal was to create a safer, more engaging environment than the existing bot, with a focus on fostering meaningful social interactions and friendships.

Subscribe to my blogposts

Get updates on my latest projects and articles directly to your inbox. No spam.

Getting Started: The Technical Foundation

I initially handled the backend development for the Telegram bot, with my friend Jack focusing on the data side of things. Here's how the backend was designed to work:

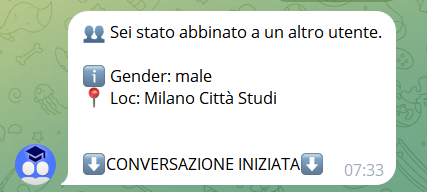

Users could access the bot and specify details like their gender, university campus (we have several across Lombardy), study program, and interests. This info wasn’t used for matching; instead, it gave the matched person a brief bio of who they were talking to.

Once in the main menu, you could click “join” to enter a pool and be randomly matched with another user. The matching was entirely random, although we had plans for a feature where you could specify preferences — unfortunately, we never got that far.

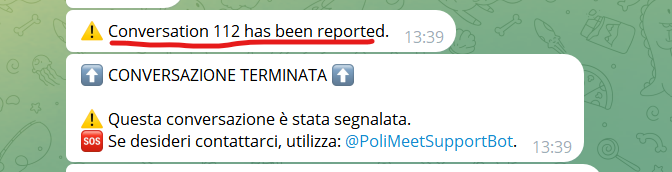

Safety First: The "Safety Report" Feature

One of the standout features of our bot was the “Safety Report.” If at any point someone felt unsafe in a conversation, they could use this button to report it. When a report was filed, the chat history was sent to admins for review. If a user was deemed harmful, we would ban them from the bot.

Other than these cases, all conversations remained anonymous. Messages weren’t stored on a server; instead, they were simply forwarded between users, so we didn’t need to worry about disk space or data privacy issues.

The First Setback: Losing Everything

After a few weeks of coding and skipping classes, the bot was almost ready to launch. However, disaster struck the morning we planned to go live.

While on the train to university, I logged into the server to make a quick fix to a bug I had found the previous night. After making the changes, I logged off and went back to sleep. When I arrived at campus and tried to access the server again, the entire script had vanished. We didn’t use version control, nor did we have any backups — everything was lost.

I desperately tried everything to recover the file, from looking for cached copies on my PC to instructing my mom on how to search my desktop at home. But it was all gone. This was a huge blow to me and my two friends, especially since we had a major Physics midterm the next day. Instead of studying, I worked tirelessly for the next 48 hours, rebuilding the bot from scratch.

In hindsight, the setback helped. Since I already had a clear picture of what the bot needed, coding the second version was quicker and better organized.

Launching PoliMeet: The Marketing Campaign

When we were finally ready to launch, we decided to go all out with an advertising campaign. Anna, one of the team members, designed awesome flyers to be distributed around the campus. We placed them near vending machines, water dispensers, microwaves, bulletin boards — anywhere we thought students would notice.

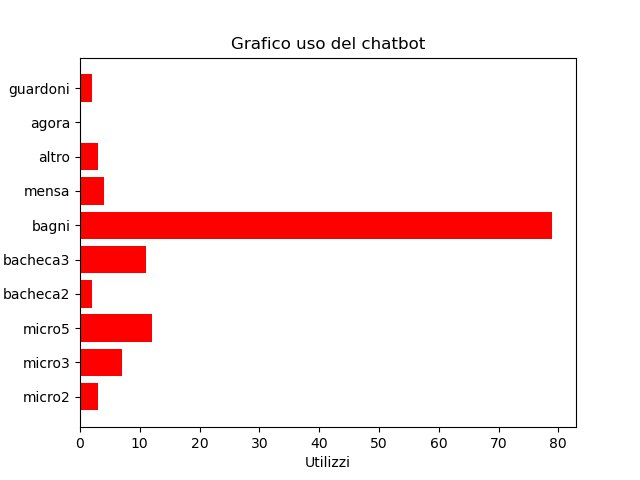

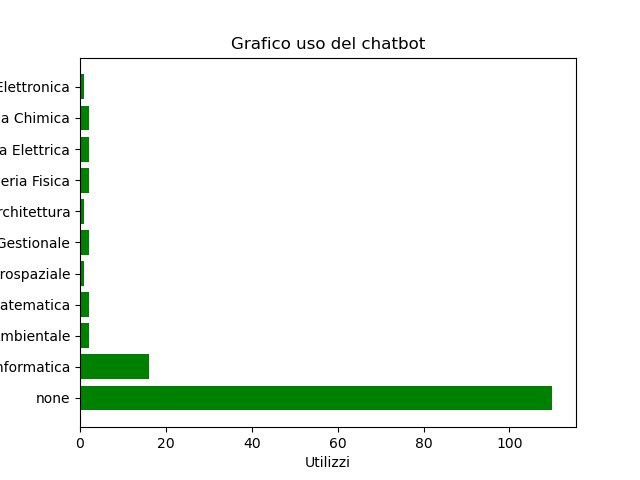

We also wanted to track which flyers were most effective. On Telegram, when you start a bot, it can read an "argument" in the URL. For example, if you use a link like https://t.me/botfather?start=CODE_HERE the bot can detect that specific code. We created different QR codes with unique arguments, like "micro5" for the microwaves in Building 5, or "bathrooms" for the stickers we put in restroom stalls. Jack was in charge of processing this data to see which locations were driving the most bot starts.

I was not surprised that the most used flyer was the "bathroom" one.

Growing Interest: PoliNetwork Reaches Out

Once the flyers and stickers were up, we started seeing activity on the bot. While we couldn’t monitor conversations for privacy reasons, we received notifications when someone started the bot, along with the location tied to their QR code.

After a few days, our project caught the attention of a university association called PoliNetwork. Anna had shared the bot link in one of their large Telegram groups, and one of the admins reached out to her.

The three of us were invited to a discussion group where PoliNetwork members mentioned they’d had a similar idea — jokingly called "PoliTinder" — but we were the first to actually build something. They even offered to review our code and potentially integrate the bot with their network to make it a more widely-used service.

Lessons Learned

Though the discussions with PoliNetwork didn’t lead to anything concrete, it was exciting to see our project gaining traction. Sadly, PoliMeet has since been discontinued, and we don’t have plans to revive it.

What we take away from this experience is invaluable: the importance of version control, the challenges of managing a project for a large community, and the sense of accomplishment that comes from seeing an idea through to the end.

PoliMeet may not have become the next big thing on campus, but it taught us some key lessons about teamwork, resilience, and the ups and downs of amateur projects.

Other members involved: